Ai Weiwei Dropping the Urn

Ai Weiwei “Dropping the Urn” – But “Where is Weiwei” Today?

Editors Note: Ai Weiwei has been arrested in Beijing and on April 4, 2011 there are fears for his safety amid a crackdown on intellectuals in China.

The catalog of Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn, Ceramic Works, 5000 BCE – 2010 CE, begins ominously, with the declaration, “…ceramics is kind of crazy. I hate ceramics… I think if you hate something too much, you have to do it. You have to use that.” His ambivalent passion has been captured in this jewel-box of an exhibition. Organized by Arcadia University Art Gallery, Glenside, Pennsylvania (February 24 – April 18, 2010) the show is currently at the Museum of Contemporary Craft (through October 30), in partnership with Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, Oregon.

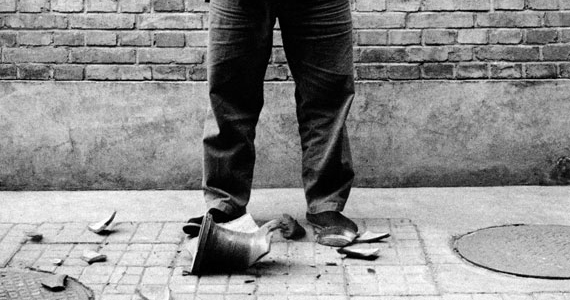

The show is named after Weiweis most iconic work, a triptych of photographs, Dropping a Han-Dynasty Urn (1995). The action makes us witnesses to the willful destruction of a superb, “museum quality” urn that had survived for 5,000 years in pristine condition. Weiwei impassively sends it crashing to its death. Urn rightly dominates the installation, a persistent reminder of Weiweis fearless, transgressive iconoclasm.

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995; triptych of gelatin silver prints, each print 49 5/8

The exhibition is small, a mere twenty works, of which ten are ceramic. The scale of each is modest, at least by Weiweis standards. At first it seems too compact to do its job. But the absence of larger works such as Bubble (2008), a 100-piece installation of blue porcelain orbs, or a forest of his seven-foot tall Color Jars (2006), is soon forgotten. The curators, Gregg Moore and Richard Torchia, have done a stealer job of selecting pivotal works that interlock to produce an expansive dialogue about Weiweis long view of culture and deliver this via its oldest messenger, ceramic art.

For an artist who claims to dislike the medium, Weiwei is certainly deeply implicated, maintaining a pottery studio with 20 skilled ceramists that is located amid the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen in the clays history, to objects that in the hands of this demon archeologist, dissect and challenge Chinas past and present, ruthlessly exposing finely crafted mythologies about art, civilization, connoisseurship and monetary value.

Even though Dropping the Urn is one of the earlier works on the exhibition, it remains his most audacious and belongs to a small group of 20th-century ceramics that have been major game-changers in the arts. This small class includes Marcel Duchamps Fountain (1917), Isamu Noguchis The Queen (1931), Meret Oppenheims fur-lined teacup Object (1936), Kazuo Yagis Walk (1954), Peter Voulkoss Rocking Pot (1956) and Jeff Koons three-handed gilded neo court porcelain, Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988).

Indeed Fountain and Urn make perfect bookends for 20th-century avant-gardism. Both created outrage, both acts were seen as offensive albeit for different reasons, and for both the ceramic component was lost, one through indifference and the other by design. They live on only as photographic documentation (courtesy of Alfred Stieglitz, in the case of Fountain).

Weiweis Urn was greeted with howls of disbelief from the culture profession, particularly the international Chinese antiquities market, for what they perceived as an act of self-indulgent barbarism, akin to book burning – and no doubt with a concern as to its consequences for their bottom line. But Weiwei calmly pointed out that that the urn, while finely potted, “was industry then and is industry now.” And he is correct; hundreds of thousands, maybe even millions were made in proto-factory situations. In other words, for the all the aura of preciousness acquired by the accretion of time (and skillful marketing), this vessel is the Iron Age equivalent of a flower pot from K-Mart and if one were to smash the latter a few millennia from now, would it be an occasion for tears?

A similar ruthless revisionism applies in three other works, Coca-Cola Vase (1997), Colored Vases (2006) and Dust to Dust (2009). The first two are Iron Age pots that have been clobbered, the first with the addition of a painted Coca Cola logo, the second by dipping a group of pots in house paint to obscure the millennia-old surface painting. Dust to Dust, one of the shows most complex pieces conceptually, is also visually the most prosaic. An undistinguished glass jar contains Neolithic pots that have been ground to dust. These three works dance nimbly backwards and forwards through time and generate multiple debates that range from cultural imperialism to mortality.

Weiwei is particularly fond of playing with clays mimetic gift, its chameleon-like ability to convincingly take on the disguise of another material, leather, wood, metal. This was originally explored in the virtuosic Yixing wares from the 15th century onwards, the first individual signed ceramic art works in China that mimicked, with eye-deceiving fidelity, wood, nuts, root vegetables, gourds, rocks, leather bags and other materials.

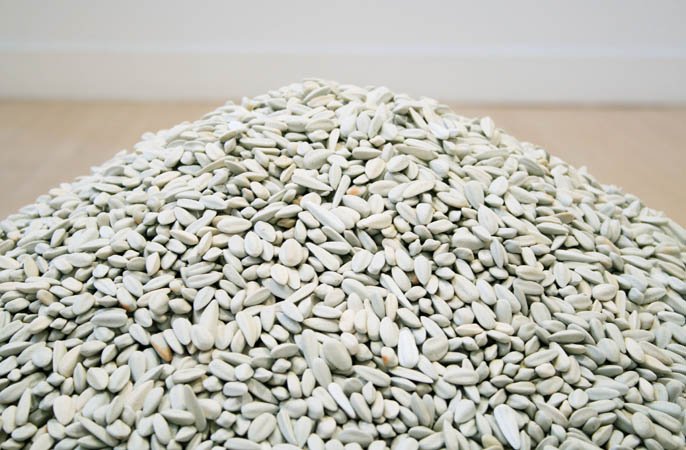

Untitled, Ai Weiwei, 2006, porcelain, 250kg of porcelain sunflower seeds.

Watermelons (2006) is a pair of lusciously glazed melon forms that from a distance appear convincingly real. (Weiwei likes to show these in fields in large numbers.) Untitled, (2006), a tours de force installation, is a pile of sunflower seeds (above), Chinas most ubiquitous snack-food, weighing exactly one ton. Each little porcelain seed is a marvel of trompe loeil craftsmanship and in subtle ways made to be even more “aesthetic” than the seeds themselves.

Untitled belongs to a popular brand of art installation that includes the “takeaways” by Felix-Gonzales Torres and Andreas Gurskys pyramids, made up of shattered ceramic facades from demolished buildings. However, in these cases the materials were found and inexpensive. Weiweis seeds are each made individually so the cost of manual input and time is immense, even profligate. This extravagance would seem counter to Weiweis egalitarianism but it reminds us that the artist is a constantly moving target, as ready to break societys rules as he is his own.

He has ascribed as many meaning to this work as he has had interviews about it but the one that seems to stick ties it to classic Communist Chinese propaganda in which “we are all sunflowers because we are facing the sun and the sun is Mao Zedong.”

Ai Weiwei, "Untitled" 2006. Porcelain sunflower seeds

The visual and contextual intelligence of this exhibition is exhilarating and all too rare these days. The installation is spare and gives each work the space in which to breathe. The book that accompanies it, like the exhibition, is of modest size- 124 pages, but every essayist and interviewer (Gregg Moore, Richard Torchia, Zhuang Hui, Philip Tinari, Glenn Adamson, Dario Gamboni, Stacey Pierson) delivers a memorable piece of writing. While it may seem unfair to single out one writer among this literary wealth, Glenn Adamsons contribution, The Real Thing”, is perhaps his best writing to date, establishing him (if there was ever any doubt) as the most insightful commentator today on the art object. The two questions Adamson poses in his essay, “Where is Weiwei?” and “When is Weiwei?” are the same queries addressed by this exemplary exhibition and answered in ways that give the viewer rational points of entry while allowing Weiweis ceramics their full voice; complex, contradictory and compelling.

is there not anyone else to write ceramic history than Garth Clark?

I find him to be a parasite whom never steps into a clay studio, fluent in words but does not do(Hamada)…he sickens me to no end.

Everything he makes should be smashed in kind and never displayed…….a putrid act of vandalism for a personal publicity stunt…..robbed everyone of a piece of history ..does not deserve to be called an artist

“Transgressive iconoclasm” is pathetic artreview/speak giving him credibility he does not deserve….start smashing HIS work and delete him from history…he has made himself irrelevant