Andean Tunics Are Dazzling Menswear 2000 Years Old

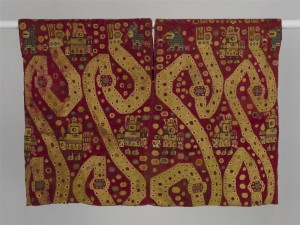

The magnificent Andean tunics on view at the Met (March 8-September 18, 2011, Michael C. Rockefeller wing) offer an eye-popping display of mens shirts from ancient to post-colonial Inka culture in Peru. As antiquities they tell a strictly visual story of time without written narrative. The exhibit represents 2000 years in which the tunics were ubiquitous in material culture, from mens daily wear to elite rulers status objects to likely warrior dress. We have seen modernist histories written that treat Andean textiles as incidental to a master narrative of 20th-century abstraction with breakthroughs starring painters Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko (and of course, Picasso, who “invented” abstraction). Re-viewing history is what is visible here. Consider by a look at this show that representational breakthroughs also occurred 400 years before the Christian era. That antiquity is not merely ruin but intense sophistication defying sound bite. Above: Tunic with Confronting Mythical Serpents.

The Andean Tunic, 400 BCE -1800 CE – organizes the textiles by half-millennia. The show speaks in toto to how archeologists and anthropologists meet up over shirts to amass modern knowledge after a century of scholarship on the objects and their variations over epochs. Gaze at them as panels of delightful visual mystery.

Two earliest tunics (400 B.C.E.) are from the Ica valley of southern Peru, one woven of cotton; the other of camelid hair. (The four Andean camelids are llama and alpaca, and the vicuña and guanaco.) Later tunics amp up the imponderables of iconography that saw Inka symbols conjoining with patterns celebrating European kings (namely, the rampant feline). Hence the show is both a celebration of time and a notice that the material history of Inka, a warrior empire, changed irrevocably after contact. The Spanish rulers in the 16th century first saw, and saw to fear, the intensely visual symbology of languages they likely could not understand. By 1780, wearing the tunics was prohibited even to the Inka regals by both the Spanish governors and the Catholic priests.

A story told by curator Julie Jones at the press preview offered that the chessboard patterned shirt (ca. 1460-1540) – with a small motif in each square – was possibly worn by chieftains soldiers as they accompanied their chief to his imprisonment.

A story told by curator Julie Jones at the press preview offered that the chessboard patterned shirt (ca. 1460-1540) – with a small motif in each square – was possibly worn by chieftains soldiers as they accompanied their chief to his imprisonment.

There is both pageant and verve . An undyed cotton tunic representing pelicans and lent by The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C is one of the stunners of the show. Its exquisite surface is as fine as any petit-point. Brilliant color in camelid tunics dyed with cochineal are incredibly contemporary and suggestive of something Lady Gaga might happily wear with blue hair.

“Symbolic meanings to the religion are not yet clear,” Julie Jones said offering that an absence of written language leaves us “at the mercy of archeology, iconography and your own imagination” to interpret the visual glyphs. Sweet mercy.

Other lenders to the show include The Cleveland Museum of Art, and two private collections.