Clyfford Still: Part Menace and Yes, Part Majesty

At the top of stairs, which rise elegantly from the lobby of the Clyfford Still Museum, is a dark red wall hung with the artist’s self portrait (PH-382) from 1940. A tall man in a black painter’s smock and tie, has angular features, intense eyes and large hands.

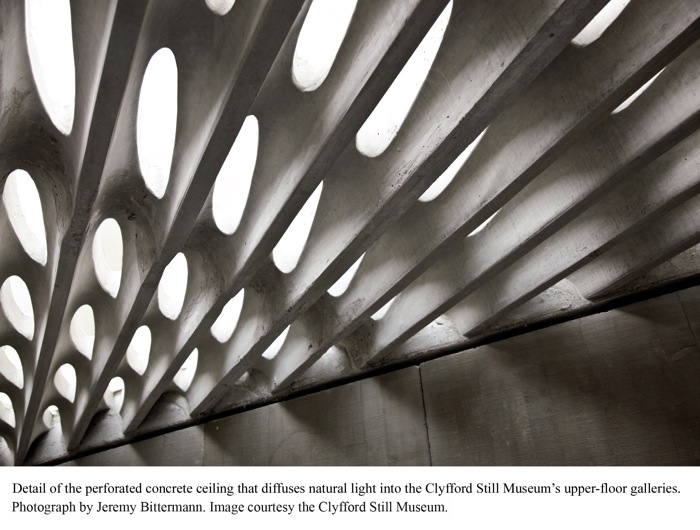

What can be known of the man who forcibly turned his back on the commercial art world in the early 1970s? This question may well be the province of the new Clyfford Still museum, which bests any other hagiographic museum dedicated to a single artist’s work, in possessing 94% of his lifetime output: 825 paintings, 1,575 works on paper and 3 sculptures. The inaugural exhibition at the new space designed by Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works Architecture, co-curated by director Dean Sobel and adjunct curator David Anfam, features 110 Still works.

Earliest is PH-45, a small still life of colorful river stones and lupine, painted in 1925 when Still was 21. This is followed by a 1927 western landscape with a factory or grain tower, a plume of smoke rising, and a vast horizon punctuated by a long, red train. Even in his earliest landscapes, Still’s affinity for color and vertical shapes is evident. He painted trains, farm workers, sweeping fields and broad skies. Then, switching to the figure, he turned nearly mannerist, in works featuring elongated faces and limbs, while exploring the physical, emotional and psychological effects of hard labor on men.

In PH-77 from Depression year 1936, blood trails down the arms of the men chaffing wheat, their bodies bent beneath a blackened sky. The grotesquery of arms nearly as long as legs prefigures the 1937 work in which men, in PH-343, begin to merge with machinery, before five years later Still moves to showing solely outlines, shapes and shadows.

1944-N No. 1 (PH-235) shows Still having made a canvas of complete abstraction, using layers of black pigment cut with a deep red outline, a hint of vivid yellow, a drip almost of white and in the lower right corner, an emerald green.

Still said that if you look “with unfettered eyes you may find forces within yourself that you didn’t realize.” One painting that continues to resonate long after standing before it is PH-129, 1949. It’s a smallish canvas, featuring thick layers of burnt umber and goldenrod sliced by storm cloud gray with the palest lavender. There are hints of hidden green and then in the upper left quadrant the merlot red and black tones that Still preferred. It was painted in San Francisco, when he taught at what is now the San Francisco Art Institute. Still claimed that behind all of his work was the figure. The tall verticals express a life force.

In gallery five, dedicated to the 1950-1961 years when Still lived in New York and painted amid AbEx brethren, the scale of works increase dramatically. These works will look familiar to viewers who have seen Stills in the Museum of Modern Art or San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, for example: jagged shapes locked in bold color fields, or raw ungessoed canvases pierced with color.

[slideshow id=54]

Two of the late paintings on view are magisterial. PH-9292 from 1974 is nearly 15 feet wide. In this horizontal canvas, the vertical gesture, expressed in Still’s signature black pigment, is more lightly applied, jutting into bare canvas, punctuated by white. There is a thin red vertical near the lower middle of the work and hints of color in dabs of magenta and yellow. The swirling motion in the canvas is like the wind blowing the jagged shapes in all directions, clockwise and counterclockwise. Not all works succeed for me, some have too much zigzag motion in them, but I left the museum realizing that Clyfford Still’s contention that his work needs to be seen all together, was correct. The gestalt is symphonic.

Still was serious about his painting and what it meant. Sobel, Anfam and others have dozens of possible future exhibitions to present yet unseen works by the artist. Scholarship, until now nonexistent will likely increase. But the question remains, though, once the school field trips come and go, and the novelty of the new wears off, will this museum with its $10 admission price be appealing to a public with a millisecond attention span more interested in snapping photos with their smartphones than actually spending a sustained time looking at the paintings as Still wanted? With an art viewing public that can go to art fairs for a viewing hypermarket, is there a contemporary art lover capable of seeing the majesty in Clyfford Still’s vision?